Disparates del género gramatical / Follies of grammatical gender

(English version below)

Disparates del género gramatical

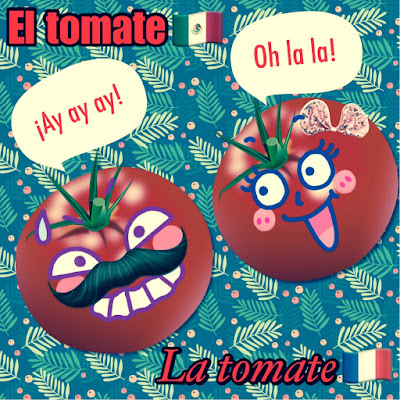

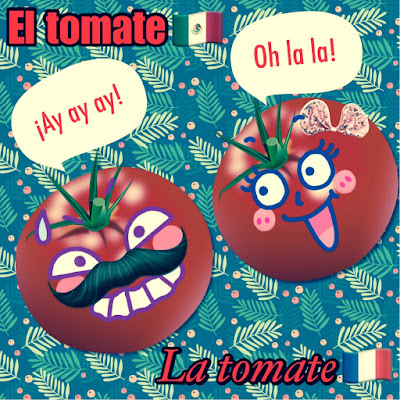

El tomate en español, la tomate en francés

El género es un aspecto esencial en la gramática de muchas lenguas del mundo, particularmente las indoeuropeas, como el español, el francés, el alemán, el griego o el ruso. En estas lenguas, palabras como "hombre" o "mujer" pertenecen respectivamente al llamado género masculino y femenino. Y las palabras que refieren a seres animados con un género biológico, suelen pertenecer al respectivo género gramatical. Así, en francés no es lo mismo "un chat" (un gato) que "une chatte¨ (una gata) y no es lo mismo estar "heureux" (feliz si eres hombre) que "heureuse" (feliz si eres mujer).

En español, las palabras masculinas suelen terminar en "o" y las femeninas en "a" y de esta manera cambiamos el género de un nombre o adjetivo para que concuerde con la persona: decimos maestro y maestra, amigo y amiga, mexicano y mexicana. En otros casos, existe una sola forma para ambos géneros y para la distinción nos valemos de los artículos: el estudiante, la estudiante.

El problema es que esta dicotomía resulta bastante lógica cuando estamos hablando de personas o seres animados con un género biológico, pero no es así cuando estamos hablando de cosas o ideas abstractas.

¿Por qué "la corbata" es femenina, por qué "el vestido" es masculino? Cierto estudiante de español tenía la idea de que "vestido" debería ser una palabra femenina porque lo usan las mujeres y "corbata" una palabra masculina porque la usan los hombres.

Bueno, ante esta suposición, conviene recordar que también hay hombres con vestidos y mujeres con corbatas, por una parte; y por otra, que no es lo mismo género gramatical que género biológico. El género gramatical es una convención arbitraria, simplemente en la lengua se decidió que "corbata" sería femenina y no importa si quien la use es femenino o no. Por otra parte, existen casos como el de la palabra "mano", que es femenina, con todo y que termina en "o" y por eso decimos "la mano" y no "el mano"; y poco importa si la mano es de hombre, mujer o quimera; la mano es femenina.

Una tendencia que ahora está muy de moda en los discursos políticos o sociales que pretenden ser más incluyentes es mencionar siempre el género femenino porque se cree que el masculino "excluye" a las mujeres. Hay que recordar que el género masculino en español en realidad es incluyente, pues se ocupa para referir a personas o animales de cualquier género (como cuando decimos "los niños son el futuro" sin que se excluya a las niñas) mientras que el femenino sí que es excluyente pues refiere únicamente a personas o animales de género femenino.

El género gramatical en español

En otros casos, hay palabras que gramaticalmente son femeninas aunque refieran a seres de cualquier género. Por eso, sin importar si eres hombre o mujer, eres "una persona" y nunca "un persono". Y lo mismo ocurre a la inversa con palabras que gramaticalmente son siempre masculinas como "individuo" o "sujeto" aunque haya quien quiera hablar de "individuas" y "sujetas".

En inglés se han simplificado la vida notablemente. La lengua perdió los géneros que tenía en su antiüedad y ahora sólo los conserva en los pronombres personales. Esto vuelve la gramática del inglés mucho más sencilla:

Español: el amigo, la amiga, los amigos, las amigas

Inglés: the friend, the friends

Si queremos especificar el género, en inglés debemos recurrir a una palabra explícita como male (masculino)o female (femenino). Sin embargo, como hemos mencionado, la tercera persona sí distingue género en inglés, con los pronombres he (él) y she (ella) así como sus formas respectivas his, him; her, hers.

Pero otras lenguas del mundo muy alejadas de las indoeuropeas no tienen género ni siquiera para el pronombre de tercera persona. Por ejemplo, en turco, o puede ser tanto "él" como "ella" o "ello". Algo similar ocurre en finés y en húngaro. Otros idiomas sin género gramatical son el japonés, el coreano y el persa. En chino "él" y "ella" se pronuncian igual y sólo la escritura es diferente.

Y sin embargo, henos aquí, las lenguas indoeuropeas, complicándoles la vida al mundo, haciéndoles escoger entre uno u otro género para cada palabra. En alemán ni siquiera se conforman con dos géneros, tienen tres: masculino, femenino y neutro. Bueno, podríamos pensar, lógicamente los hombres y animales machos entran en el género masculino, las mujeres y animales hembras entran en el género femenino y las cosas e ideas abstractas son neutras, ¿no?

Pues no. En alemán, las cosas e ideas abstractas también pueden ser femeninas, masculinas o neutras. Y a veces ni siquiera existe la lógica que uno esperaría porque la palabra para "muchacha" no es femenina sino neutra (das Mädchen), esto debido a su terminación. Y peor aún, en alemán los artículos masculino, femenino, neutro y plural se declinan dependiendo de la función de la palabra en una oración. Y es aquí cuando la gramática del alemán hace que el español parezca un juego de niños. Y el inglés ni se diga...

Artículos en alemán y en inglés...¿¿¿Por qué???

¿Quién dijo que "el amor" es masculino y "la vida" es femenina? No hay una razón lógica. Simplemente las palabras tenían que pertenecer a uno de los dos géneros y la elección fue arbitraria. ¿O no?

¿Por qué será que las cosas tienen un género en una lengua y otro en otra lengua? ¿Qué les pasa a los franceses que dicen la tomate? ¿Cómo podemos permitir que le cambien el género a los tomates? Y luego a la nariz la toman por masculina y le llaman le nez...

Y sin embargo, al ser el francés y el español lenguas romance, la mayoría de las palabras tienen el mismo género que heredaron del latín, que así como el alemán, tenía también un género neutro que tanto el español como el francés perdieron. Muchas veces, la razón por la cual alguna palabra en francés tiene diferente género que en español es porque en latín la palabra en cuestión era neutra y una lengua la asimiló como femenina y otra como masculina.

En algo estamos de acuerdo, tanto en francés como en español la luna (la lune) es femenina y el sol (le soleil) es masculino, de eso no hay duda. Si representamos al sol y a la luna como seres animados, probablemente diremos que la luna es mujer y el sol hombre. Pero los alemanes no estarían de acuerdo. Y es que en alemán el sol es femenino (die Sonne) y la luna es masculina (der Mond)

Una maestra de alemán nos contaba que en cierta fiesta organizada por alemanes, los baños de hombres tenían una luna y los de mujeres un sol. Y como era de esperarse, todos los mexicanos se fueron a meter al baño equivocado.

Es curioso que en inglés, aunque las palabras no tienen género, conservan hasta cierto punto la visión de la luna como un hombre (si bien alternarla con una personificación femenina también es bastante común). Esto puede explicarse porque tanto el alemán como el inglés son lenguas germánicas, y el inglés antiguo compartía esta categorización de sol femenino y luna masculina. En México vemos un conejo en la luna, en inglés hablan del "hombre en la luna" (man in the Moon).

¿Pero por qué una cultura como la germánica decidió ver en la luna una entidad masculina y en el sol una femenina, mientras que una cultura como la latina hizo lo contrario? Tal vez la respuesta esté en la mitología... esa madre primigenia de culturas y religiones. Y si las lenguas están inmersas en la cultura, o como diría Humboldt, la lengua es el espíritu de los pueblos, no es de extrañar que la cosmovisión mitológica de cada cultura haya tenido un rol fundamental en la lengua (¿o viceversa?).

En la mitología grecorromana se nos habla de una diosa de la luna, Selene para los griegos y Luna para los romanos, quien, coronada con una media luna, conducía en el cielo nocturno con su carro de plata tirado por bueyes blancos. Al terminar su viaje, su hermano, Helios para los griegos, o Sol para los romanos, coronado con la aureola de sol, conducía con sus caballos que arrojaban fuego, Flegonte (ardiente), Aetón (resplandeciente), Pirois (ígneo) y Éoo (amanecer).

Selene y Helios

Asimismo, la diosa Artemisa (o Diana) y su hermano gemelo Apolo, también serían identificados como deidades de la luna y del sol respectivamente.

Por su parte, en la mitología nórdica propia de los pueblos germánicos, el dios de la luna es Máni, y es el hermano de Sól, la diosa del sol. Ambos son perseguidos por lobos a través del cielo, y en su recorrido crean el día y la noche para contar los años de los hombres.

Podemos notar cómo diversos fenómenos o elementos de la naturaleza como el sol y la luna, han sido imaginados como entidades masculinas o femeninas en diferentes culturas donde la mitología los atribuye a un dios o diosa particular. En muchos casos había dioses para casi todas las cosas. El panteón romano era increíblemente grande. Y si el género de los dioses es diferente en cada cultura, es natural que el de las cosas también.

Cuando era niño me gustaba jugar en la mesa con los cubiertos. La cuchara, con un velo de servilleta, se casaba con el tenedor y el cuchillo era el malvado rival que llegaba a interrumpir la boda. Qué curioso ver cuantas asociaciones fabricaba mi mente infantil, determinada desde entonces por mi lengua nativa y mi contexto histórico, al momento de imaginar un juego tan aparentemente simple. El género gramatical de las cosas nos hace imaginarlas de una forma específica. Por supuesto que la cuchara, con esas curvas, debía ser la dama de la discordia en mi pequeña telenovela, y el cuchillo, con esos filos peligrosos, tenía que ser el villano.

La lengua, así como la biología o la historia, nos determina más de lo que nos gustaría aceptar.

Quisiéramos creer que somos libres pero no podemos escapar de las reglas de nuestra propia naturaleza, que nunca escogimos. Vinimos al mundo sin pedirlo y se nos impuso una nacionalidad, una religión, una genética, y por supuesto, una lengua.

La llave en español, "el" llave en alemán

Juguemos a cambiar la lengua. Ese género arbitrario que la lengua impuso, hay que transformarlo. Ahora digamos el cucharo, la tenedora, el servilleto, el meso, el sillo, la vasa, el cocino.

Pero eso nos traería inevitables problemas. Podríamos decir cucharo si queremos, pero si le cambiamos el género a otras palabras podríamos cambiar el significado radicalmente. No es lo mismo un puerto que una puerta, un rato que una rata, un copo que una copa, un pedo que una peda.

Si quisiéramos transformar nuestra lengua, mejor sería eliminar el género por completo. Mejor sería eliminar los verbos irregulares, esas conjugaciones disparatadas, esas etimologías contradictorias, esas polisemias confusas, y demás ambigüedades.

En este mismo blog he publicado sobre posibles reformas ortográficas para simplificar el inglés o el francés. Pero al final las convenciones son más fuertes y aún más en la gramática o el vocabulario que en la ortografía. Y por eso esas intenciones feministas de decir niñxs o niñes para ser más incluyentes no tienen éxito en la vida cotidiana.

Según ciertas teorías, las lenguas necesariamente tienen que ser difíciles. Si una lengua es aparentemente muy fácil en alguna área, necesariamente habrá otra área donde represente un gran reto. El chino es muy fácil en su gramática pero no hablemos de la escritura o la pronunciación. La pronunciación del español es relativamente sencilla y la ortografía relativamente transparente pero no hablemos de la gramática.

El chiste parece ser complicarse la vida, porque somos complicados. Se multiplicaron las lenguas tras el episodio de la Torre de Babel, y ahora el mundo es una gran confusión donde cada quien habla en lenguajes más extraños y complicados para los demás. Y esos lenguajes no solo son los idiomas, también son nuestras ideologías y creencias...

Volviendo al tema de los dioses y las cosas, en muchas de las creencias religiosas más primitivas es común atribuir a todas las cosas un alma o conciencia, lo cual se conoce como animismo. Dentro de esas concepciones se considera que todo está vivo, incluyendo las piedras, el mar, la tierra, el aire.

Podemos pensar que en nuestro género gramatical persiste un poco de esa concepción divina y animista de las cosas, donde todo tiene un alma y una personificación que puede ser femenina, masculina o neutra. Y así como la visión de las divinidades varía en cada religión, la visión de los géneros varía en cada lengua.

Es interesante corroborar con estos ejemplos cómo varía la interpretación del mundo dependiendo de nuestro contexto. Religiones, lenguas y culturas, todas ellas son muy diferentes, pero al final de cuentas, con ellas todos estamos tratando de comunicar y descifrar lo mismo, un mundo extraño y maravilloso en donde la divinidad, con el nombre, el género o los atributos que sean, no deja de manifestarse en todas las cosas y en todas las ideas, en todo lo que percibimos y en todo lo que somos.

La torre de Babel

Ferdinandus

***

Follies of grammatical gender

A tomato is masculine in Spanish and feminine in French

Gender is an essential aspect of the grammar of many languages in the world, particularly Indo-European, such as Spanish, French, German, Greek or Russian. In these languages, words like "man" or "woman" belong respectively to the so-called masculine and feminine genders and words that refer to animate beings with a biological gender, usually belong to the respective grammatical gender. Thus, in French it's not the same a chat (a male cat) than une chatte (a female cat) and it's not the same being heureux (happy if you are man) than heureuse (happy if you are a woman).

In Spanish, masculine words usually end in "o" and the feminine ones in "a" and in this way we can change the gender of a noun or adjective to agree with the person: we say maestro (male teacher) and maestra, (female teacher), amigo (male friend) and amiga, (female friend) mexicano (Mexican man) and mexicana (Mexican woman). In other cases, there is only one form for both genders and for the distinction we use articles: el estudiante (the male student) la estudiante (the female student).

In Spanish, masculine words usually end in "o" and the feminine ones in "a" and in this way we can change the gender of a noun or adjective to agree with the person: we say maestro (male teacher) and maestra, (female teacher), amigo (male friend) and amiga, (female friend) mexicano (Mexican man) and mexicana (Mexican woman). In other cases, there is only one form for both genders and for the distinction we use articles: el estudiante (the male student) la estudiante (the female student).

The problem is that this dichotomy is quite logical when we are talking about people or animate beings with a biological gender, but this is not so when we are talking about abstract ideas or things.

Why is la corbata (the tie) feminine, why is el vestido (the dress) masculine? A certain Spanish student had the idea that "dress" should be a feminine word because women use it and "tie" a masculine word because it is used by men.

Well, before this supposition, it is worth remembering that there are also men in dresses and women in ties, on the one hand; and on the other hand, that grammatical gender is not the same as biological gender. Grammatical gender is an arbitrary convention, in the language it was simply decided that "tie" would be feminine and it doesn't matter if the wearer is feminine or not. On the other hand, there are cases like the word mano (hand), which is feminine, even though it ends in "o" and that is why we say "la mano" and not "el mano"; and it does not matter whether the hand is a man's, a woman's or a chimera's. The hand is feminine.

A Spanish trend that is now very fashionable in political or social discourses trying to be more inclusive is to always mention the female gender because it is believed that the masculine "excludes" women. It is necessary to clarify that the masculine gender in Spanish is generic and inclusive, since we use it to refer to people or animals of any gender (as when we say los niños son el futuro - "the children are the future" without excluding the girls -niñas) whereas the feminine is indeed exclusive because it only refers to persons or animals of feminine gender.

Why is la corbata (the tie) feminine, why is el vestido (the dress) masculine? A certain Spanish student had the idea that "dress" should be a feminine word because women use it and "tie" a masculine word because it is used by men.

Well, before this supposition, it is worth remembering that there are also men in dresses and women in ties, on the one hand; and on the other hand, that grammatical gender is not the same as biological gender. Grammatical gender is an arbitrary convention, in the language it was simply decided that "tie" would be feminine and it doesn't matter if the wearer is feminine or not. On the other hand, there are cases like the word mano (hand), which is feminine, even though it ends in "o" and that is why we say "la mano" and not "el mano"; and it does not matter whether the hand is a man's, a woman's or a chimera's. The hand is feminine.

A Spanish trend that is now very fashionable in political or social discourses trying to be more inclusive is to always mention the female gender because it is believed that the masculine "excludes" women. It is necessary to clarify that the masculine gender in Spanish is generic and inclusive, since we use it to refer to people or animals of any gender (as when we say los niños son el futuro - "the children are the future" without excluding the girls -niñas) whereas the feminine is indeed exclusive because it only refers to persons or animals of feminine gender.

Grammatical gender in Spanish

In other cases, there are words that are grammatically femenine but refer to beings of any gender. So, regardless of whether you are male or female, you are una persona (a person) and never "un persono". And the same thing happens in the reverse with words that are grammatically always masculine like individuo (individual) or sujeto (subject/guy) although there are those who want to speak of "individuas" and "sujetas".

In English life has been greatly simplified. The language lost the genders it had in its antiquity and now only retains them in personal pronouns. This makes English grammar much simpler:

Spanish: el amigo, la amiga, los amigos, las amigas

English: the friend, the friends

If we want to specify the gender, in English we must resort to an explicit word like male or female. However, as we have mentioned, the third person does distinguish gender in English, with the pronouns he and she, as well as their respective forms his, him; her, hers.

However, other languages of the world very far from the Indo-European have no gender even for the third-person pronoun. For example, in Turkish, o can be either "he", "she" or "it". Something similar happens in Finnish and Hungarian. Other languages without grammatical gender are Japanese, Korean and Persian. In Chinese "he" and "she" are pronounced the same and only the writing is different.

And yet, here are the Indo-European languages, complicating the life of the world, making them choose between one gender and the other for each word. In German even these two genders are not enough, they have three: masculine, feminine and neuter. Well, we might think, logically men and male animals belong to the male gender, women and female animals belong to the female gender and abstract things and ideas are neuter, right?

Well, no. In German, abstract ideas and things can also be feminine, masculine, or neuter. And sometimes there's no logic as we would expect because the word for "girl" is not feminine but neuter (das Mädchen), this because of its termination. And even worse, in German the masculine, feminine, neuter and plural articles are declined depending on the function of the word in a sentence. And this is where the grammar of German makes Spanish look like a child's play. And let's not talk about English...

In English life has been greatly simplified. The language lost the genders it had in its antiquity and now only retains them in personal pronouns. This makes English grammar much simpler:

Spanish: el amigo, la amiga, los amigos, las amigas

English: the friend, the friends

If we want to specify the gender, in English we must resort to an explicit word like male or female. However, as we have mentioned, the third person does distinguish gender in English, with the pronouns he and she, as well as their respective forms his, him; her, hers.

However, other languages of the world very far from the Indo-European have no gender even for the third-person pronoun. For example, in Turkish, o can be either "he", "she" or "it". Something similar happens in Finnish and Hungarian. Other languages without grammatical gender are Japanese, Korean and Persian. In Chinese "he" and "she" are pronounced the same and only the writing is different.

And yet, here are the Indo-European languages, complicating the life of the world, making them choose between one gender and the other for each word. In German even these two genders are not enough, they have three: masculine, feminine and neuter. Well, we might think, logically men and male animals belong to the male gender, women and female animals belong to the female gender and abstract things and ideas are neuter, right?

Well, no. In German, abstract ideas and things can also be feminine, masculine, or neuter. And sometimes there's no logic as we would expect because the word for "girl" is not feminine but neuter (das Mädchen), this because of its termination. And even worse, in German the masculine, feminine, neuter and plural articles are declined depending on the function of the word in a sentence. And this is where the grammar of German makes Spanish look like a child's play. And let's not talk about English...

WHY???

Who said that in Spanish love (el amor) was masculine and life (la vida) was feminine? There's no logical reason. Words simply had to belong to one of the two genders and the choice was arbitrary. Or not?

Why is it that things have one gender in one language and another in another language? What happens to the French who say la tomate? How can Spanish speakers allow them to change tomatoes' gender? And then they treat the nose as masculine and call him le nez... - in Spanish it's feminine.

And yet, being French and Spanish Romance languages, most words have the same genre they inherited from Latin, which like German, also had a neuter gender that both Spanish and French lost. Many times, the reason why a word in French has a different gender than in Spanish is because in Latin the word in question was neuter and one language assimilated it as feminine and the other as masculine.

In something we agree, in both French and Spanish the moon (la lune and la luna) is feminine and the sun (le soleil and el sol) is masculine, there's no doubt about that. If we represent the sun and the moon as animate beings in these languages, we will probably say that the moon is a woman and the sun is a man. But the Germans wouldn't agree. And this is because in German the sun is feminine (die Sonne) and the moon is masculine (der Mond)

A German teacher told us that in a party organized by Germans, the men's rooms had a moon and the women's rooms had a sun. And as expected, all Mexicans got into the wrong bathroom.

It's curious that in English, although words have no gender, they retain to some extent the vision of the moon as a man (although alternating it with a feminine personification is also quite common). This can be explained by the fact that both German and English are Germanic languages, and Old English shared this categorization of a feminine sun and a masculine moon. In Mexico we see a rabbit on the moon, in English people speak about the "man in the moon".

But why did a culture like the Germanic one decided to see on the moon a male entity and in the sun a female one, while a culture like the Latin one did the opposite?

Perhaps the answer lies in mythology ... that primal mother of cultures and religions. And if languages are immersed in culture, or as Humboldt might say, language is the spirit of peoples; it's not surprising that the mythological worldview of each culture has played a fundamental role in language (or viceversa?)

In Greco-Roman mythology we speak of a moon goddess, Selene to the Greeks, and Luna to the Romans, who, crowned with a crescent moon, drove in the night sky with her silver chariot drawn by white oxen. At the end of her journey, his brother, Helios to the Greeks, or Sol to the Romans, crowned with a sun's aeroela, drove with his fire throwing horses, Phlegon (burning), Aethon (blazing), Pyrois (igneous) and Eous (dawn).

Why is it that things have one gender in one language and another in another language? What happens to the French who say la tomate? How can Spanish speakers allow them to change tomatoes' gender? And then they treat the nose as masculine and call him le nez... - in Spanish it's feminine.

And yet, being French and Spanish Romance languages, most words have the same genre they inherited from Latin, which like German, also had a neuter gender that both Spanish and French lost. Many times, the reason why a word in French has a different gender than in Spanish is because in Latin the word in question was neuter and one language assimilated it as feminine and the other as masculine.

In something we agree, in both French and Spanish the moon (la lune and la luna) is feminine and the sun (le soleil and el sol) is masculine, there's no doubt about that. If we represent the sun and the moon as animate beings in these languages, we will probably say that the moon is a woman and the sun is a man. But the Germans wouldn't agree. And this is because in German the sun is feminine (die Sonne) and the moon is masculine (der Mond)

A German teacher told us that in a party organized by Germans, the men's rooms had a moon and the women's rooms had a sun. And as expected, all Mexicans got into the wrong bathroom.

It's curious that in English, although words have no gender, they retain to some extent the vision of the moon as a man (although alternating it with a feminine personification is also quite common). This can be explained by the fact that both German and English are Germanic languages, and Old English shared this categorization of a feminine sun and a masculine moon. In Mexico we see a rabbit on the moon, in English people speak about the "man in the moon".

But why did a culture like the Germanic one decided to see on the moon a male entity and in the sun a female one, while a culture like the Latin one did the opposite?

Perhaps the answer lies in mythology ... that primal mother of cultures and religions. And if languages are immersed in culture, or as Humboldt might say, language is the spirit of peoples; it's not surprising that the mythological worldview of each culture has played a fundamental role in language (or viceversa?)

In Greco-Roman mythology we speak of a moon goddess, Selene to the Greeks, and Luna to the Romans, who, crowned with a crescent moon, drove in the night sky with her silver chariot drawn by white oxen. At the end of her journey, his brother, Helios to the Greeks, or Sol to the Romans, crowned with a sun's aeroela, drove with his fire throwing horses, Phlegon (burning), Aethon (blazing), Pyrois (igneous) and Eous (dawn).

Selene and Helios

Likewise, the goddess Artemis (or Diana) and her twin brother Apollo, would also be identified as deities of the moon and the sun respectively.

On the other hand, in the Norse mythology, proper to the Germanic peoples, the god of the moon is Máni, and is the brother of Só, the goddess of the sun. Both are pursued by wolves across the sky, and in their journey they create day and night to tell the years of men.

We can see how various phenomena or elements of nature like the sun and the moon have been imagined as male or female entities in different cultures where mythology attributes them to a particular god or goddess. In many cases there were gods for almost everything. The Roman Pantheon was unbelievably large. And if the gender of gods is different in each culture, it's natural that the gender of things should be as well.

When I was a child I liked to play at the table with silverware. The spoon, with a veil of napkin, married the fork and the knife was the evil rival who came to interrupt the wedding. How curious to see how many associations made my child mind, determined since then by my native language and my historical context, at the time of imagining such a seemingly simple game. The grammatical gender of things makes us imagine them in a specific way. Of course the spoon, with those curves, must be the lady of discord in my little soap opera, and the knife, with those dangerous edges, had to be the villain.

Language, as well as biology or history, determines us more than we would like to accept.

We would like to believe that we are free but we cannot escape the rules of our own nature, which we never chose. We came to the world without asking for it and we were imposed a nationality, a religion, a genetics, and of course, a language.

On the other hand, in the Norse mythology, proper to the Germanic peoples, the god of the moon is Máni, and is the brother of Só, the goddess of the sun. Both are pursued by wolves across the sky, and in their journey they create day and night to tell the years of men.

We can see how various phenomena or elements of nature like the sun and the moon have been imagined as male or female entities in different cultures where mythology attributes them to a particular god or goddess. In many cases there were gods for almost everything. The Roman Pantheon was unbelievably large. And if the gender of gods is different in each culture, it's natural that the gender of things should be as well.

When I was a child I liked to play at the table with silverware. The spoon, with a veil of napkin, married the fork and the knife was the evil rival who came to interrupt the wedding. How curious to see how many associations made my child mind, determined since then by my native language and my historical context, at the time of imagining such a seemingly simple game. The grammatical gender of things makes us imagine them in a specific way. Of course the spoon, with those curves, must be the lady of discord in my little soap opera, and the knife, with those dangerous edges, had to be the villain.

Language, as well as biology or history, determines us more than we would like to accept.

We would like to believe that we are free but we cannot escape the rules of our own nature, which we never chose. We came to the world without asking for it and we were imposed a nationality, a religion, a genetics, and of course, a language.

Feminine key in Spanish, masculine key in German

Let's play to change the language. That arbitrary gender that the language imposed, it has to be transformed. Now let's say in Spanish el cucharo instead of la cuchara (the spoon), la tenedora instead of el tenedor (the fork) el servilleto instead of la servilleta (the napkin), etc.

But that would inevitably bring us problems. We could say el cucharo if we want, but if we change the gender of other words we could change the meaning radically. Puerto (port) is not the same as puerta (door) un rato (a while) is not the same as rata (rat), copo (snowflake) is not the same as copa (wine glass) pedo (vulgar: fart) is not the same as peda (vulgar: binge).

If we wanted to transform our language, it would be better to eliminate gender altogether. It would be better to eliminate irregular verbs, such disparate conjugations, contradictory etymologies, confusing polysemies, and other ambiguities.

In this same blog I have posted about possible orthographic reforms to simplify English and French. But in the end conventions are stronger and even more so in grammar or vocabulary than in spelling. And that is why those feminist intentions in Spanish of saying niñxs or niñes instead of niños in order to be more inclusive don't succeed in everyday life.

According to certain theories, languages necessarily have to be difficult. If a language is apparently very easy in some area, there will necessarily be another area where it represents a great challenge. Chinese is very easy on grammar but let's not talk about writing or pronunciation. The pronunciation of Spanish is relatively simple and the spelling is relatively transparent but let's not talk about grammar.

The issue seems to be complicating life, because we are complicated. Languages multiplied after the episode of the Tower of Babel, and now the world is a great confusion where everyone speaks in languages that are stranger and more complicated for others. And those languages are not only spoken languages, they are also our ideologies and beliefs...

Again on the subject of gods and things, in many of the most primitive religious beliefs it is common to attribute to all things a soul or consciousness, which is known as animism. Within these conceptions everything is considered alive, including stones, the sea, the earth, the air.

We may think that in the grammatical gender there persists a little of that divine and animistic conception of things, where everything has a soul and a personification that can be feminine, masculine or neuter. And just as the vision of the divinities varies in each religion, the vision of the genders varies in each language.

It is interesting to corroborate with these examples how the interpretation of the world varies depending on our context.

Religions, languages and cultures, they are all very different, but in the end, with them we are all trying to communicate and decipher the same; a strange and wonderful world where the divinity, with whatever name, gender or attributes, doesn't cease to manifest itself in all things and in all ideas, in all that we perceive and in all that we are.

But that would inevitably bring us problems. We could say el cucharo if we want, but if we change the gender of other words we could change the meaning radically. Puerto (port) is not the same as puerta (door) un rato (a while) is not the same as rata (rat), copo (snowflake) is not the same as copa (wine glass) pedo (vulgar: fart) is not the same as peda (vulgar: binge).

If we wanted to transform our language, it would be better to eliminate gender altogether. It would be better to eliminate irregular verbs, such disparate conjugations, contradictory etymologies, confusing polysemies, and other ambiguities.

In this same blog I have posted about possible orthographic reforms to simplify English and French. But in the end conventions are stronger and even more so in grammar or vocabulary than in spelling. And that is why those feminist intentions in Spanish of saying niñxs or niñes instead of niños in order to be more inclusive don't succeed in everyday life.

According to certain theories, languages necessarily have to be difficult. If a language is apparently very easy in some area, there will necessarily be another area where it represents a great challenge. Chinese is very easy on grammar but let's not talk about writing or pronunciation. The pronunciation of Spanish is relatively simple and the spelling is relatively transparent but let's not talk about grammar.

The issue seems to be complicating life, because we are complicated. Languages multiplied after the episode of the Tower of Babel, and now the world is a great confusion where everyone speaks in languages that are stranger and more complicated for others. And those languages are not only spoken languages, they are also our ideologies and beliefs...

Again on the subject of gods and things, in many of the most primitive religious beliefs it is common to attribute to all things a soul or consciousness, which is known as animism. Within these conceptions everything is considered alive, including stones, the sea, the earth, the air.

We may think that in the grammatical gender there persists a little of that divine and animistic conception of things, where everything has a soul and a personification that can be feminine, masculine or neuter. And just as the vision of the divinities varies in each religion, the vision of the genders varies in each language.

It is interesting to corroborate with these examples how the interpretation of the world varies depending on our context.

Religions, languages and cultures, they are all very different, but in the end, with them we are all trying to communicate and decipher the same; a strange and wonderful world where the divinity, with whatever name, gender or attributes, doesn't cease to manifest itself in all things and in all ideas, in all that we perceive and in all that we are.

The tower of Babel

Ferdinandus

Este comentario ha sido eliminado por el autor.

ResponderBorrarmuchas gracias por tu blog!

ResponderBorrara proposito, que libros estas utilizando con alumnos en niveles avanzados (C1-C2)? parece que hay pocos relevantes publicados en dos ultimos años.