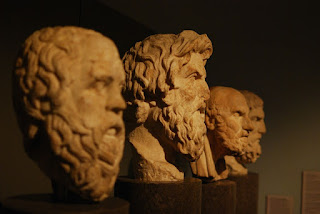

El alma y las ideas / Soul and ideas

(English version below)

El alma y las ideas

El alma y las ideas

En el diálogo de Platón Fedón o del alma se desarrolla la idea

del alma y de su imortalidad. La historia de Sócrates, sentenciado a morir

injustamente pero que acepta su sentencia con tranquilidad debido a su fe en la

inmortalidad del alma, se nos presenta como un pretexto para que los personajes

del diálogo expresen sus ideas y busquen comprobar la validez de la creencia de

Sócrates.

Resulta

muy importante el ejercicio de descontextualizarnos en la medida de lo posible

para tratar de acceder al pensamiento de los griegos antiguos. La

influencia de nuestro contexto pesa mucho cuando buscamos acceder sin

preconcepciones a cualquier

texto lejano a nuestro historia y cultura. En estos tiempos en

que el método científico impera en el conocimiento, la forma en que los filósofos antiguos llegaban a

conclusiones tajantes por medio de argumentaciones puede desconcertarnos.

Sin embargo, no podemos sino recordar que existen áreas del conocimiento que

siguen siendo terreno dominante de la filosofía, donde los argumentos y

las opiniones son tan válidos como el método científico. La labor hermenéutica

nos exige buscar más preguntas que respuestas, ¿y qué mejor tema para este

ejercicio que el alma? ¿Realmente

existe el alma? ¿Es el alma inmortal? Para tratar de responder estas preguntas no

podemos recurrir a pruebas objetivas sino a argumentos y opiniones más o menos subjetivas.

En

el diálogo de Platón, Sócrates se presenta como el arquetipo del filósofo; el

hombre que ha logrado desprender el alma de su cuerpo por medio del amor a la sabiduría, que produce en las personas la percepción de la

trascendencia. Por eso Sócrates no le teme a la muerte, él sabe que lo realmente

importante es el alma; el cuerpo es sólo un envase perecedero, y como el alma

ha sido cultivada con la sabiduría, ella será capaz de liberarse de la prisión

del cuerpo y acceder al mundo supremo de las ideas.

¿Pero

de dónde nos viene esta idea de que el alma es algo ajeno al cuerpo? Basta con

revisar la antropología y veremos que el ser humano ha buscado a través de

distintos tiempos y espacios encontrar una respuesta a su existencia y al

sentido de la misma. Pensar que tenemos un alma que puede persistir sin nuestro

cuerpo nos consuela ante la temible realidad de la muerte. Por eso

prácticamente todas las religiones y las culturas del mundo giran en torno a

estos conceptos de vida y muerte; y

tienen una manera distinta de discutir acerca del alma.

Es

interesante contrastar la idea del alma en distintas culturas. Contrastemos oriente y occidente; un ejemplo lo encontramos en los populares mangas y animes japoneses, en los cuales nos podemos

encontrar con una amalgama de ideas que fusionan conceptos tradicionales de la

cultura japonesa con los de la cultura europea y americana. Podemos citar

muchos referentes en los que podemos contrastar la visión del mundo espiritual en

ambas culturas.

Un ejemplo interesante es Inuyasha, donde se trata la idea de la reencarnación y del alma en

una historia sobre una viajera en el tiempo al mundo mítico y sobrenatural del

Japón feudal. La protagonista, Kagome Higurashi, resulta ser la reencarnación

de una sacerdotisa llamada Kikyou, que posteriormente será resucitada por una

bruja. La serie nos explica que las dos personas pueden coexistir debido a que

varias almas de Kagome fueron transmitidas a Kikyou. Posteriormente Kikyou, que alberga sentimientos de venganza y

rencor por la forma en que murió, será una antagonista importante de la serie,

y estará condenada a alimentarse de las almas de muchas jóvenes para

sobrevivir.

La

serie Mushishi es otro ejemplo

interesante para apreciar la visión japonesa de lo espiritual. En esta serie se

nos habla de la existencia de los mushi, criaturas

que se encuentran en una región inferior a los humanos, más cercanos a los

fantasmas; seres que simplemente existen más allá del mundo terrenal y que no

pueden ser vistos por la gente ordinaria. En el segundo capítulo de la serie

nos encontramos con la historia de una joven que se ha enfermado de ceguera

debido a que un mushi se metió en sus ojos. La historia nos propone una

visión acerca de los llamados segundos párpados, algunas personas tienen la habilidad de cerrar

su segundo párpado para ver por completo en obscuridad. Y en esa obscuridad

pueden acceder al río de luz, en una experiencia mística de la que a veces es

difícil escapar, y por la que la joven perdió la vista. ¿No es ese río de luz

un poco como ese mundo de las ideas del que habla Platón? De acuerdo con Platón,

nuestra alma estaría atada a un mundo al que realmente no pertenece, “usando”

varios cuerpos en su camino mientras busca liberarse de ese mundo terrenal.

La reencarnación, que solemos relacionar con el pensamiento

oriental aparece incluso en las religiones judeocristianas. El cristianismo actual gira en torno a la

creencia de la resucitación de Cristo al tercer día, y en el cristianismo primitivo se aceptaba la reencarnación.

El

pensamiento griego también tenía sus ideas al respecto. En el Fedón ya se discute el tema cuando se

cuestiona por qué los seres humanos nacemos con conocimientos muy establecidos

que nos permiten comprender el mundo en que nos rodeamos e ideas abstractas

como la belleza. El diálogo propone que tenemos una memoria que precede a

nuestra existencia en esta vida, con nuestro cuerpo actual. Nuestra alma ha

existido anteriormente y esa proposición se establece como una realidad

incuestionable casi desde el principio del diálogo.

La

cuestión que preocupa a los discípulos de Sócrates a lo largo del diálogo es

otra. Si bien no se cuestiona que el alma haya existido anteriormente en una

realidad superior a la terrenal, se cuestiona si el alma no morirá naturalmente

después de “usar” muchos cuerpos. El objetivo de Sócrates es convencer a sus

discípulos de que el alma es en efecto inmortal.

Sin

duda alguna es muy interesante la forma en que Sócrates consigue llegar a esa

conclusión mediante premisas lógicas. Primero se

establece como algo fehaciente el hecho de que las cosas contrarias tienen

siempre en sí a sus contrarias, no pueden dejarse penetrar por la presencia que

es contraria a ellas; los números pares siempre serán contrarios a los impares,

y por lo tanto son incompatibles entre sí. A

través de este razonamiento, se termina por concluir que el alma debe ser

inmortal, ya que ella es en sí misma lo contrario a la muerte. Es imposible que

en una esencia penetre la idea contraria

de lo que constituye su esencia.

¿Qué

hace que el cuerpo esté vivo?, pregunta Sócrates. Es el alma. Por consiguiente

el alma, así como los números pares que siempre llevan su esencia de números

pares, debe llevar siempre consigo la vida que es su esencia constituyente. Al

ser la muerte lo contrario a la vida, el alma no consentirá nunca la muerte,

que es contraria a su esencia.

La

idea de que el alma es lo que hace que el cuerpo esté vivo nos regresa a la

pregunta que nos habíamos planteado en un principio sobre por qué parece tan

natural la división del alma y el cuerpo en casi todas las ideologías del

mundo. Evidentemente, desde tiempos ancestrales, los seres humanos se

preguntaban ¿Por qué este cuerpo muerto ya no puede moverse, ya no tiene vida?

¿Cuál es la diferencia entre este ser y yo? La ciencia nos dirá que la

diferencia entre un cuerpo vivo y uno muerto es que los órganos del primero

continúan en funcionamiento mientras que los del segundo no. Pero en realidad no

es así de simple. Lo insólito es preguntarnos ¿por qué los órganos de

este ser simplemente dejaron de funcionar? Y nuevamente se nos podrá responder con

las causas fisiológicas, el deterioro de los órganos que provocó la muerte del

organismo. ¿Pero por qué se deterioró ese organismo? Y las preguntas pueden

continuar infinitamente. En esencia, no podemos responder por qué alguien vive

y alguien muere. Hay algo que le falta al muerto que el vivo aún tiene. Y a eso

le hemos llamado alma.

El

término suele intercambiarse con espíritu y mente. La mente que ocupa el

cerebro, la esencia espiritual que ocupa la materia orgánica. Aquello que

representa nuestro mundo interno, nuestras ideas, nuestros pensamientos,

nuestras preferencias; lo que nos hace ser lo que somos. Y por supuesto, no

queremos pensar que cuando el cuerpo muera, lo que somos morirá también.

Ésa era una de las preocupaciones de Miguel de Unamuno, quien mencionaba

que él, con su traje gris que tanto lo caracterizaba, no podía dejar de ser él mismo, con su traje gris, al morir. En su novela Niebla,

nos encontramos con el autor dialogando con su personaje principal, que se

resiste a aceptar la muerte que el autor ha decidido para él. El juego entre la

realidad y la creación resulta muy evocador. Es el material de

numerosos referentes culturales, de los que basta recordar la clásica trilogía

cinematográfica de ciencia ficción Matrix,

en la que se propone que nuestras vidas no son sino una realidad virtual

programada por las máquinas que nos han dominado en el mundo real.

Es

imposible comprobar que lo que vemos y sentimos es real y que no estamos siendo

engañados por nuestros sentidos. O que incluso lo que percibimos como real no es

sino lo que pensamos que es real. La

teoría de las expectativas sostiene que lo que el cerebro espera que ocurrirá,

tiende a ocurrir, y es la razón por la cual los placebos son efectivos como

tratamientos médicos reales. Estas curiosas habilidades del cerebro, que muchas

veces desafían los criterios establecidos por la medicina, nos llevan a la común frase de que el

cerebro – donde residiría la mente – es el área más desconocida de nuestro

cuerpo; y no es de extrañar ya que estamos tratando de entender nuestro cerebro

con él mismo.

¿Cómo

comprobar que lo que juzgamos real lo es? ¿Cómo osamos hablar de objetividad

cuando todo lo percibimos con nuestros subjetivos sentidos? Como dice esa

canción de Caifanes, “Afuera no existe,

sólo adentro”. Sería imposible salirnos de nosotros mismos para poder

entender ese mundo exterior que tratamos de medir, clasificar y resumir para

nuestro mejor entendimiento.

Recordemos

la alegoría de la caverna de Platón, que ejemplifica su visión sobre el mundo

de las ideas. Según esta alegoría, los

seres humanos somos como un prisionero en una caverna, todo lo que vemos son

sombras, proyecciones del mundo exterior, donde realmente están las esencias y

no sólo las apariencias. Según la filosofía platónica, nuestro cuerpo nos

impide acceder a la esencia; vivimos en un mundo de apariencias y sólo tras la

muerte podrá el alma trascender a ese mundo real en el que residen las ideas.

Un

mundo ajeno a lo material, un mundo meramente espiritual ha sido la búsqueda de

muchas de las religiones y filosofías de los seres humanos. La experiencia del

Nirvana, entendido como un estado de liberación absoluta del sufrimiento del

alma en su ciclo de reencarnaciones es un concepto vital en el budismo y el

hinduismo y nos recuerda a ese mundo de las ideas. El paraíso judeocristiano, entendido

como el descanso y el goce eterno del alma tras el sufrimiento en la tierra,

es otra versión de esa liberación del alma.

Finalmente, todas las religiones hablan sobre lo mismo. Todas buscan responder en

cierta medida, ¿qué es el alma, qué es eso que nos hace ser lo que somos? ¿Y

realmente será posible para nosotros encontrar la realidad, el mundo de las

ideas, el mundo espiritual al que realmente pertenecemos? Es ésa la búsqueda

incansable del ser humano, manifestada en todas sus acciones, en la cultura, el arte y, por supuesto, la filosofía.

Soul and ideas

In Plato's dialogue, Phaedo or On the soul, the idea of the soul and its immortality is developed. The story of Socrates, unfairly sentenced to death but accepting calmly his sentence due to his faith on the immortality of soul, it's presented as an excuse for the dialogue's characters to express their ideas and try to prove the validity of Socrate's belief.

The exercise of decontextualization, where possible, turns out as very important to access the though of the ancient Greeks. The influence of our context weighs heavily when we try to access without preconceptions to any text distant to our history and culture. In these times when the scientific method reign in knowledge, the way the ancient philosophers came to categorical conclusions by means of argumentations can disconcert us. However, we cannot but remember that there are reas of knowledge that are still a ground ruled by Philosophy, in which arguments and opinions are as valid as the scientific method. The work of Hermeneutics requires us to look for more questions than answers, and what a better topic for this exercise than the soul? Does the soul really exist? Is the soul immortal? To try to answer this questions we can't resort to objective proves but to arguments more or less subjective.

In Platon's dialogue, Socrates is presented as the archetype of the philosopher; a man who has succeeded in detaching his soul from his body by means of the love to wisdom, which produces in people the perception of transcendence. That's why Socrates is not afraid of death, he knows that what really matters is the soul; the body is just a perishable package, and as the soul has been cultivated with wisdom, it will be able to break free from the prison of body and access the supreme world of ideas.

But where does this idea of the soul as something strange to the body come from? It suffices to review Anthropology and we'll see that humans have tried trough many times and spaces to find an answer to their existence and its meaning. To think that we have a soul that can persist without our body comforts us against the frightening reality of death. That's why practically all religions and cultures of the world revolve around these concepts of life and death, and they have a different way to discuss about soul.

It's interesting to contrast the idea of soul in different cultures. Let's contrast East and West; we can find an example in the popular mangas and animes, where we can find an amalgam of ideas that fuze traditional concepts of Japanese culture with those of European and American culture. We can quote many referents where we can contrast a vision of the spiritual world in both cultures.

A good example is Inuyasha, that deals with the ideas of reincarnation and soul in a story about a time traveler in the mythical and supernatural world of feudal Japan. The protagonist, Kagome Higurashi, turns out to be the reincarnation of a priestess called Kikyou, who will be subsequently resuscitated by a witch. The series explains that both persons can coexist because some souls of Kagome were transferred to Kikyou. Subsequently, Kikyiou, who houses feelings of revenge and resentment for her way of dying, will be an important antagonist in the series, and she will be condemned to feed on the souls of many young girls in order to survive. The idea of many souls in the same body contrasts with our vision of an only and absolute soul.

Mushishi is another example to appreciate the Japanes vision of the spiritual. This series deals with the existence of mushi, creatures that reside in an inferior region to humans, closer to ghosts: beings that simply exist beyond the earthly word and cannot be seen by ordinary people. In the second episode of the series we meet a young girl who is sick because a mushi got into her eyes. The story proposes a vision about the so-called second eyelids. Some poeple have the ability of closing their second eyelid so they can see in complete darkness. And in this darkness they can access the river of light, in a mystical experience from wich sometimes it is difficult to escape, and because of which the girl lost her sight. Isn't that river of light a little like the world of ideas Platon talks about? According to him, our sould would be tied to a world where it doesn't really belongs, "using" bodies in its way while it tries to break free from this earthly world.

Mushishi is another example to appreciate the Japanes vision of the spiritual. This series deals with the existence of mushi, creatures that reside in an inferior region to humans, closer to ghosts: beings that simply exist beyond the earthly word and cannot be seen by ordinary people. In the second episode of the series we meet a young girl who is sick because a mushi got into her eyes. The story proposes a vision about the so-called second eyelids. Some poeple have the ability of closing their second eyelid so they can see in complete darkness. And in this darkness they can access the river of light, in a mystical experience from wich sometimes it is difficult to escape, and because of which the girl lost her sight. Isn't that river of light a little like the world of ideas Platon talks about? According to him, our sould would be tied to a world where it doesn't really belongs, "using" bodies in its way while it tries to break free from this earthly world.

Reincarnation, that we generally connect with Eastern thought appears even in the Jewish-Christian religions. Current Christianity revolves around the belief of the resurrection of Christ on the third day, and early Christianity accepted reincarnation.

Greek thought had also its views thereon. In Phaedo the theme is already discussed when it is questioned why humans are born with very established knowledges that allows us to understand the world where we live as well as abstract ideas like beauty. The dialogue proposes that we have a memory preceding our existence in this life, with this current body. Our soul has existed previously and that proposition is set as an unquestionable reality alms from the beginning of the dialogue.

The issue that worries to Socrates' disciples throughout the dialogue is other. While it's not questioned that the soul existed previously in a reality superior to the earthly world, it's questioned whether the soul would naturally die after "using" many bodies. Socrates' goal is to convince his disciples that the soul is indeed immortal.

Without doubt, it is very interesting how Socrates succeeds to come to that conclusion through logical premises. First, it is established as a reliable proof the fact that all things have always in themselves their opposites, they can't allow to be penetrated by the presence of their opposites; even numbers will be always opposed to odd numbers, and so they are incompatible. Through this reasoning, one ends up concluding that the soul must be immortal, as it is in itself the opposite of death.

What makes the body to be alive? asks Socrates. That's the soul. Consequently, the soul, as even numbers that always carry their odd number essence, must carry always life, which is its constituent essence. As death is the opposite of life, the soul won't consent ever death, contrary to its essence.

The idea that what makes the body to be alive is the soul leads us back to the question we had raised at first about why it seems so natural the division of soul and body in almost all the world's ideologies. Of course, from ancient times, human beings questioned "why this dead body doesn't move anymore? What's the difference between this being and me? Science would say that the difference between a living body and a dead one is that the organs of the former still work while those of the latter don't. But it's not that simple. The unusual is to ask why the organs of that being just stopped working? Again we can answer with the physiological causes, the deterioration of the organs caused the death of the organism. But what deteriorated that organism? And the questions can continue infinitely. In essence, we cannot answer why somebody lives and another one dies. There is something that is missing un the dead that the living still have. And that's what we have called soul.

The term is interchangeable with spirit an mind. The mind that takes up the brain, the spirit that takes up the organic matter. That thing that represents our inner world, our ideas, our thoughts, our preferences; what makes us being what we are. And of course, we don't want to think that when the body dies, what we are will also die.

That was one of the worries of Miguel de Unamuno, who said that he, with his characteristic gray suit, couldn't stop being himself, with his gray suit, after dying. In his novel Niebla, we find the author dialoguing with his main character, who opposes the death that the author has decided for him. The game between reality and creation is very evocative. It is the material of numerous cultural referents, like the classical cinematographic trilogy of science fiction Matrix, that proposes that our lives are not but a virtual reality programmed by the machines that have dominated the real world.

It's impossible to prove that what we see and feel is real and that we are not being fooled by our senses. Or even that what we perceive as real is not but what we think is real. The theory of expectations asserts that what our brain expects that will happen, tends to happen, and that's the reason why placebos are as effective as real medical treatments. This curious abilities of our brain, that often defy the criteria of medicine, lead us to the common phrase that our brain - where mind would reside - is the most unknown area of our body; and it's not a surprise since we are trying to understand our brain with itself.

How to prove that what we pass for real is indeed real? How do we dare to talk about objectivity when we perceive everything with our own subjective senses? As that song by Caifanes says: “Afuera no existe, sólo adentro” (outside doesn't exist, only inside). It will be impossible to get out of ourselves in order to understand that external world that we try to measure, classify and synthetise for our better understanding.

Let's remember the allegory of the cave by Plato, which exemplifies his vision on the world of ideas. According to this allegory, human beings are like a prisoner in a cave, everything we see are shadows, projections of the outside world, where the real essences are and not just the appearances. According to platonic philosophy, our body prevents us from accessing the essence; we live in a world of appearances and only after death our soul will be able to transcend to that real world where ideas reside. A world far from the physical, a merely spiritual world has been the search of many religions and philosophies of human beings. The experience of Nirvana, understood as a state of absolute liberation from the suffering of the soul in its cycle of reincarnations is a vital concept in Buddhism and Hinduism and reminds us of that world of ideas. The Jewish-Christian paradise, understood as the rest and the eternal joy of the soul after the suffering in the earth, is another vision of this soul's liberation.

Finally, all religions talk about the same. They all try to answer to some extent, what is soul? what is this that makes us being who we are? And it will be really possible for us to find reality, the world of ideas, the spiritual world where we really belong? That is the tireless quest of the human being, expressed in all their actions, in culture, art and, of course, philosophy.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario